Nicole Zihua Zhang (張梓華)

initially published in ARTFORUM China in 2021. see: https://www.artforum.com.cn/interviews/13636

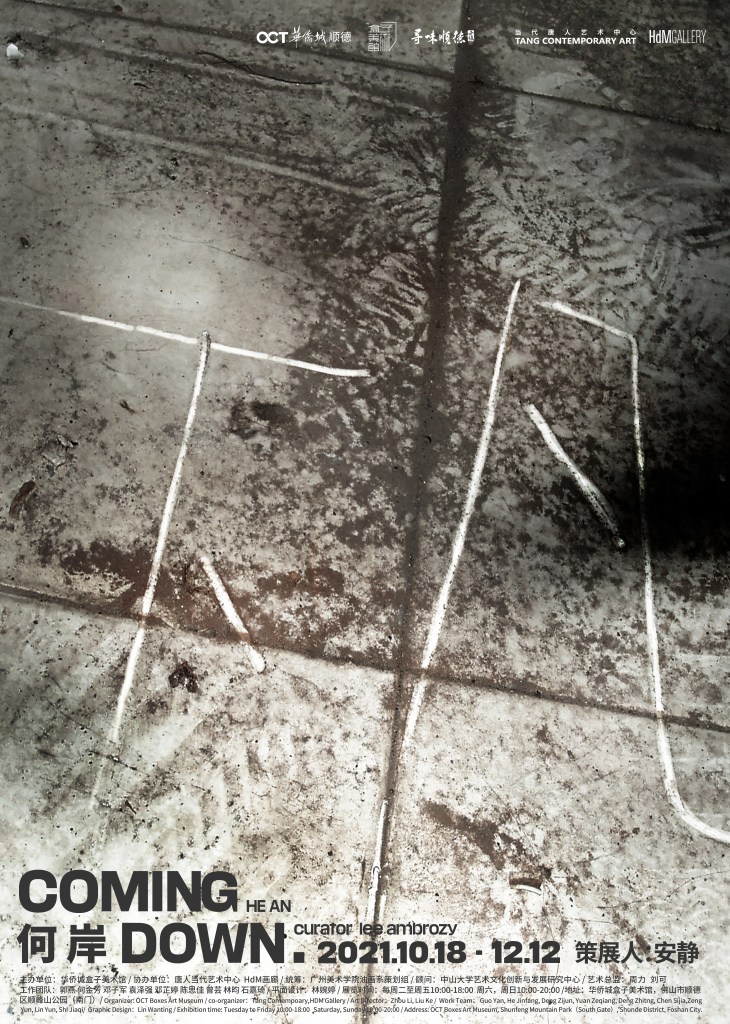

Editor’s Note: He An’s practice consistently manifests in monumental installations, in which contrasts are generated through embedded details, temperature shifts, or mechanical sound. These devices create an “allure” or a certain “literariness.” His latest solo exhibition Coming Down at Foshan OCT Boxes Art Museum may at first glance resemble a Futurist return in the twenty-first century. Yet, as this interview demonstrates, what He An seeks to probe through the exploration and deployment of diverse industrial materials is not a futuristic fantasy, but rather the concrete human condition and the weight of life itself. The exhibition remains on view until 12 December.

The title Coming Down was chosen in dialogue with curator An Jing. The English rendering conveys most directly the sense of weight inherent in the Chinese phrase xiafan. In a broader sense, it articulates a shared earthly experience: every life is a “coming down,” every life bears weight.

The initial conception of the exhibition emerged in the aftermath of the most severe period of the pandemic. I noticed that few artists in China were looking back upon, or articulating, the direct impact of the pandemic on their own sensibilities. For me, however, it was not something that could easily be left behind. As a native of Wuhan, even though I was not physically present there in 2020, I nonetheless lived through the entire process. Such collective endurance calls for a metaphysical enquiry; to put it plainly, art must also give voice to anger. That anger persists in a latent state, and art becomes the means of expression. The exhibition’s title and every fragment of its works—helmets, car doors, railings, fire escapes—are infused with the imagery of the pandemic and the virus. I have always cared deeply about the artist’s subjective perception, and about the responsibility of transmuting that perception into art as a form of critique. In this case, the intent was to enable visitors to feel the artist’s acute sensitivity in facing the pandemic society. On this basis, discussions of the industrial materials and their significance can take shape.

I am particularly drawn to the narrative and perspectival relations between artworks and exhibition architecture. Each presentation is installed differently, but perspective is always a thread running through. In this exhibition, I adopted a perspective with broken or angled lines, intended to evoke a “cosmic language” distinct from the earthly one. Just as the English word faraway carries a certain surreal inflection, the perspectival relations here diverge from conventional parallel perspective. This is why the exhibition lighting is so dim: only such treatment can engender this sense of distance—otherwise the viewer would simply perceive actual, measurable space.

In fact, I am not interested in science fiction or cosmology. What compels me are the exceptions and unpredictabilities of life itself. The space-like ambience created through the interplay of works and architecture is a means of emphasising another register of perceptual illusion.

Many of the works are bound up with memory. I grew up with a window air conditioner at home—cheap, easy to install—and I still recall its droning “rumble” vividly. Its appearance in the work arose when I once encountered a black-and-white product photograph of such a unit, which jolted me into recognising it as both a language and material. Another artist I greatly admire, Ima-Abasi Okon, has used a row of industrial air conditioners as multi-channel sound players. I liked this piece enormously; perhaps subconsciously I also wished to underscore the air-conditioning unit as a body.

In Ocean (2021), two plastic pearls were taken from a pair of jeans and placed behind the granite-textured rock that pierces a car door. James Lee Byars exhibited a work at the Red Brick Art Museum in which a round stone was cut in half, with two tiny gold beads resting on its surface. The beads condensed thought, their glimmers merging with the quartz flecks in the stone, evoking both wonder and gravity. My use of two plastic pearls glued to rock is a homage to him, yet also a humorous gesture among artists. I intentionally rendered his “spirituality” in a Pop-inflected, tongue-in-cheek manner. Similarly, the stone element in Coming Down (2021) pays homage to Joel Shapiro. To be frank, I rarely premeditate creative decisions. Some works are made for other artists to see, some for myself, particularly when refining conceptual and linguistic concerns. For audiences, I insist upon interpretation as a drifting state—one that may even lead to paradox.

I regard myself as a Wuqu Daoist—Wuqu being the martial counterpart to the literary star Wenqu. The Wuqu Daoist must cultivate a skill akin to “slaying dragons.” This “dragon” is not a fixed entity but a symbolic embodiment of natural forces, a metaphor one must discover and narrate. In the process, one is locked in combat between heaven and earth. “Heaven” grants legitimacy, and one is answerable only to it—whether we name it sky, space, Taiyi, or logos. In antiquity, the mortality rate of Wuqu Daoists was high: they confronted disasters thousands of miles away, representing the gods in calming seas and subduing destructive natural forces, always at risk of perishing in waves or fire. Success brought greater power and accumulated heavenly virtue, but the overseer was never a master or peer—only oneself, or the “heaven” acknowledged by the Wuqu Daoist. This operates on a symbolic plane. When asked why some works seem to be made “only for myself,” I believe this offers the most fitting answer.

Interview by Zhang Zihua