On “Ami Lien and Enzo Camacho: Offerings for Escalante”

by Nicole Zihua Zhang

–

Review_

–

For viewers growing up in the Pearl River Delta in Guangdong, their first encounter with the Philippines was the dried Cebu mangoes that can be found in imported snack shops, and the women who migrated to Hong Kong to provide domestic services. However, we never understood: economic globalization has not brought social life to the Philippines. On the contrary, people living in this country at this time are trapped in the intersection of neocolonialism and political violence. They have long faced the issues of food sovereignty and land justice. Ami Lien and Enzo Camacho’s solo exhibition ‘Offerings for Escalante’[1] combines the artistic expressions of video, handmade paper collages and light installations to explore the ecology of Negros Island in the Philippines, the history of the sugar plantations and the oppressive social structures behind them. using the Escalante massacre as a starting point, provides historical and contemporary evidence for examining the relationship between the state apparatus and the coexistence of people and the natural environment. The exhibition, which was part of the Glasgow International project and was exhibited at the Glasgow Museum of Modern Art (GoMA), documents the artistic duo’s long-term research on the Philippines and their latest practice in which their socio-political awareness has evolved.

对于成长在广东珠三角的人来说,与菲律宾的初识是进口零食店都会上架的宿雾芒果干,以及移居到香港提供家政服务的女性。然而,我们却不曾了解:经济全球化并没有带动菲律宾的社会生活,恰恰相反,此时此地生活在这一国度的人正困囿于新殖民主义和政治暴力的交叉影响中,他们长期以来都面临粮食主权和土地正义的问题。连洁(Ami Lien)和恩佐·卡马乔(Enzo Camacho)的个展“献给埃斯卡兰特” (Offerings for Escalante)通过结合影像、手工纸本拼贴画和灯光装置的艺术表现形式,围绕菲律宾内格罗斯岛(Negros)的自然生态、蔗糖种植园历史及其背后的压迫性社会结构,以埃斯卡兰特屠杀事件作为引子,为我们审视国家机器以及人与自然环境的共存关系提供了历史和现实证据。展览作为格拉斯哥国际(Glasgow International)项目的一部份,于格拉斯哥现代艺术美术馆(GoMA)展出,记录了这一艺术组合对菲律宾的长期研究以及他们的社会政治意识在创作中演化的最新实践。

Walking into the exhibition hall is like diving into the sleep of a giant. The threshold space directly opposite the entrance, consisting of two suspended installations, Compost Light and six large pieces of mounted rice paper, guides the viewer through a ‘rite of passage’ in which they walk from the centre outwards in this black box. The light from the two semi-spherical installations, which are suspended in mid-air, passes through onion-skin paper and is reflected by magnifying glasses and multi-faceted revolving mirrors onto the rice paper to create a constantly moving, ghostly play of light and shadow. The shadows take on abstract, dancing, and at the same time fragmented shapes of life due to the prominence of the onion skin plant nerves. The counterpart to this mesmerising installation is the disco atmosphere lights used by the farmers of the collective farming movement ‘bungkalan’[2] when they seek pleasure at night. In order to resist the abuses of the manorial system that originated in the late Spanish colonial period, these farmers responded to food security issues through collective action of cultivating the small plots of land left idle by the manor owners, and to defend their right to self-determination of the land. Their conflict with vested interests did not ease, but intensified, often leading to various degrees of political violence[3]. Here, artists Lian Jie and Enzo capture the symbols that represent the collective desires and aspirations of these farmers, subverting our stereotypical preconceptions of social movement groups. The alluring lights and mysterious shadows are so captivating that the viewer is unable to calmly examine the specific social situation. Instead, it is as if they have fallen into the subtle whirlpool of emptiness created by the artists and find it difficult to extricate themselves.

走进展厅仿佛是潜入到一个巨人的睡梦中。正对着门口的、由两个悬挂的装置《堆肥灯光》和6块悬置着的大型宣纸所构成的阈限空间,引导着观者在这个黑盒子里完成一个由中心向外行走的“过渡仪式”(Rites De Passage)。这两个在半空的装置通过射灯所散发的光穿过洋葱皮做成的纸,再由放大镜和多面自转的镜子反射到宣纸上形成了不断移动的幽灵般的光影。因为洋葱皮植物神经的凸显而使这些影子注入了抽象的、舞动的、同时又是割裂的生命形状。这令人恍惚的装置的对应物则是集体耕种运动“bungkalan” 的农民们在夜间寻求欢愉时所使用的迪斯科氛围灯。为了抵抗源自于西班牙殖民末期的庄园制度的弊端,这些农民通过耕种庄园主闲置的小块土地的集体行为来应对粮食安全问题,以及维护自己的土地自决权。他们与既得利益者的矛盾并没有因此得到缓和,而是愈演愈烈,经常引发成各种不同程度的政治暴力事件 。于此,艺术家连洁和恩佐捕捉的却是代表这些农民集体欲望和憧憬的象征物,颠覆了我们对社会运动群体的刻板预设。诱惑迷人的灯光、神秘吊诡的影子,观者置身其中,很难对具体的社会情景进行冷静的审视,反之,就像是掉入到艺术家制造的虚空、微妙的漩涡里,难以抽离。

When faced with complex political realities, does the use of such a romanticised aesthetic treatment with simple symbols lack direct meaning and obscure the artist’s subjective position? And how should creators deal with their socio-political awareness and grasp the relationship between artistic expression and social care? Just as the viewer is dazzled by the looming ‘ghosts’, the voices of interviewees who survived the Escalante massacre can be heard from time to time in the depths of the exhibition hall, guiding us out of our confused state. As these voices, which contain both local languages and English, approach, one can see a nearly one-hour-long video work, Langit Lupa, standing before one’s eyes. Here, the artist has used a method of ‘critical fabulation’[4] to restructure and establish an imagination of the narrative of a tragic historical event. Starting with the overlapping layers of the plantation, images of Negros Island gradually appear, including streams, water buffaloes, and abandoned fields. Behind the seemingly peaceful scenes, different first-person accounts alternate, retracing the colonial history of the sugar cane plantations and mills, as well as the different first-hand accounts of the Escalante massacre that took place in 1985. Between each witness account of the massacre, the artist uses a dynamic phytogram[5] as a link. Using a microscope and light-sensitive emulsion, the fibrous tissue of various plants and organic materials on the island is activated and magnified, and then presented as a plant diagram through the visual effects of colour film. The interlaced plant meridians and faintly discernible outlines of stems and leaves flashed quickly before the eyes, not only setting the emotional tone of the entire film, but also leaving room for the viewer to empathise and reflect. In addition, the artist invited local children to perform the eyewitness testimonies. They are the only characters in the film and also serve as symbolic signs of these oral histories throughout the work. They play in the sugar cane fields, reenact the massacre commemoration ceremony, and collectively mourn the victims who were only 14 years old in the cemetery. During his stay on Negros Island, the artist conducted empirical research on the collected documentary archives, and at the same time reactivated the interpretation of the Escalante massacre through a semi-documentary and semi-fictional approach. Combining oral history, real scenes and fictional plots, he created an experimental film interweaving the past, present and future, which powerfully conveys the subject’s loss of a certain social reality. Who is the main character here? Is it the oppressed Filipino peasant community? Is it the survivors of the massacre who are speaking out? Is it the child representing the future? Is it the artist? Or is it us, the viewer? The ghosts of history are entangled with the people and things of the present, allegorically suggesting that the tragedy has not ended, but is constantly recurring and being repeated.

面对复杂的政治现实时,利用简单的符号做出如此浪漫化的审美处理,是否缺乏直接意义并模糊了艺术家的主观立场?而创作者又该如何处理他们的社会政治意识,如何把握艺术表现与社会关怀的关系?正当观者被影影绰绰的“幽灵”包围而眩晕之时,展厅深处会不时传出从埃斯卡兰特屠杀中幸存的受访者说话的声音,引导着我们从迷惑的境况中抽离出来。随着这些夹杂着当地语言和英语的声音迈进,可以看到一部将近一小时的影像作品《天/地》(Langit Lupa)矗立眼前。在这里,艺术家以一种“批判性虚构” (Critical Fabulation)的方式对一段令人悲恸的历史事件的叙述进行了重组、建立了想象。从层层叠叠的种植园开始,逐渐呈现着小溪、水牛、荒废的田地等建构内格罗斯岛的画面。看似平和的景象背后,交替出现着不同的亲述声音追溯甘蔗种植园和糖厂的殖民历史,以及发生在1985年的埃斯卡兰特屠杀的不同亲历。每一段屠杀事件目击者的证词之间,艺术家以动态的植物显影图 (Phytogram)作为承接,使用显微镜和感光乳剂将岛上多种植物和有机材料的纤维组织进行激活、放大,再通过彩色胶片的视觉效果将一个个植物图谱呈现出来。交错的植物经络和依稀可辨的茎叶轮廓快速地在眼前闪现,不仅渲染了整部影片的情感基调,还给观者留有情感共鸣和反刍的空间。此外,艺术家邀请了当地的小朋友对目击者的证词进行演绎。他们是片中唯一出现的人物,同时作为这些口述历史的象征符号贯穿着整部作品。他们在蔗园嬉戏、重演屠杀纪念活动仪式、在墓园对年仅14岁的牺牲者进行集体悼念。艺术家在内格罗斯岛旅居期间对所收集的文献档案进行实证考究,同时通过半纪实半虚构的方式重新激活埃斯卡兰特屠杀事件的解读方式,将口述历史、现实场景和虚构情节结合起来创作了一个交织着过去、现在和未来的实验影像,有力地传达了主体人物对某种社会现实的失落。而这里的主体人物是谁?是受压迫的菲律宾农民群体?是正在发声的屠杀事件幸存者?是代表未来的小孩?是艺术家?还是作为观者的我们?历史的幽灵和当下的人事物纠缠在一起,寓言式地暗示着悲剧并没有结束,而是在不断轮回、重演。

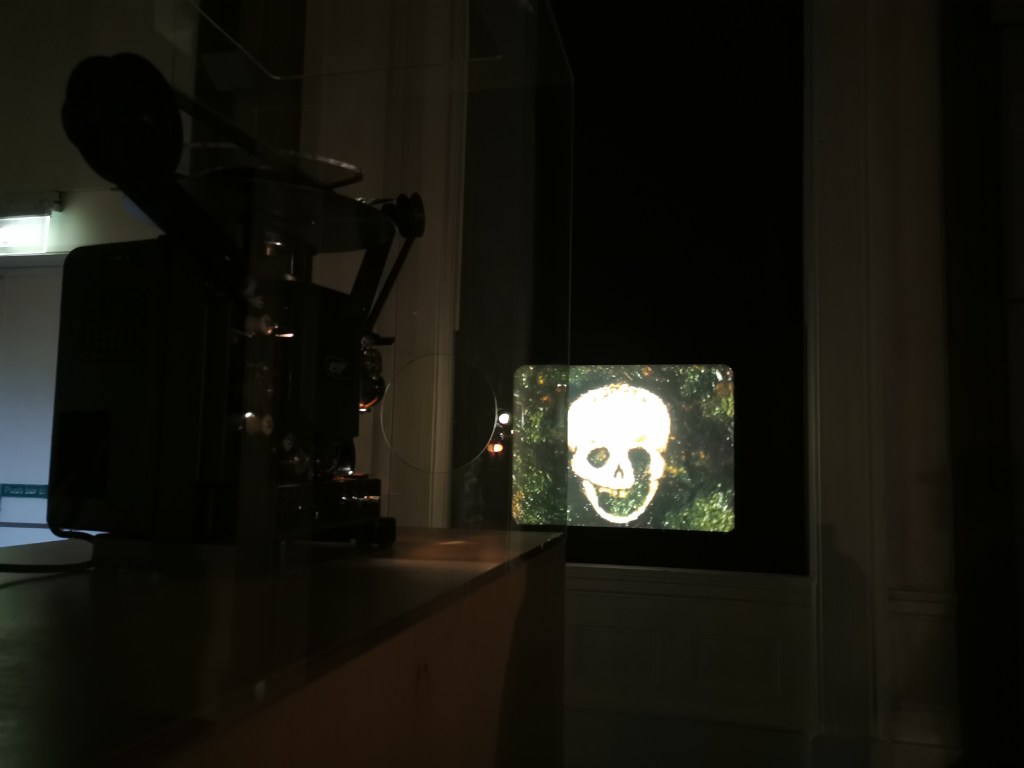

In addition to ambiguity, anger and mourning, artists Lian Jie and Enzo are also embracing the land of Negros with a light heart. They temporarily put aside artistic interventions on political violence and refrain from romanticising the victims or survivors. Instead, they approach the natural ecology, collect various tropical plants on the island to make special handmade paper, and combine popular visual rhetoric such as butterflies, flames and Sacred Hearts to create paintings. This series of works is arranged around the exhibition hall, and together they form an imaginary ecological landscape with religious mystery. At the end of the exhibition, one encounters another interesting imagination: the artist continues to use these folkloric images, playfully using wet plant pulp to create a stop-motion animation, ‘Decomposition Animation,’ to depict the fermentation process of organic compost. The skull at the end of the animation cleverly dialogues with the ‘ghostly’ shadows in ‘Compost Light’, as if to respond to the fate of the sugar mill workers, who, like these microorganisms in their cycle of life and death, were tied to the ‘dead time’[6] (tiempo muerto) of the sugar cane plantations with their hourly wage labour. The narrative of the entire exhibition seems to contrast with reality: it has a beginning but no end.

除了暧昧、愤怒和哀悼,艺术家连洁和恩佐还以轻盈的姿态来拥抱内格罗斯岛的大地。他们暂时放下对政治暴力的艺术干预,也不去将受害者或幸存者进行浪漫化,而是从自然生态切入,收集岛上各种不同的热带植物制成特殊的手工纸本,结合流行的视觉修辞如蝴蝶、火焰、圣心进行绘画创作。这一系列作品并被布置在展厅四周,它们共同构成了一幅具有宗教神秘色彩的想象性生态景观。在展览的尾声,人们会邂逅另一种趣味的想象:艺术家继续沿用这些带有民俗性的图像,戏谑地用湿植物纸浆制作的定格动画《分解动画》,去刻画有机堆肥的发酵过程。动画最后的骷髅头图像又巧妙地与《堆肥灯光》的“幽灵”光影对话,仿佛回应着糖厂工人的命运就像这些微生物的生死循环,他们钟点工式的劳动收入与甘蔗种植园的“死亡时间” (tiempo muerto)息息相关。整个展览的叙事仿佛与现实对照:设定了开头,却没有结尾。

Notes_

[1] Lien and Camacho’s solo exhibition ‘Offerings for Escalante’ was exhibited in Glasgow, Hong Kong’s Para Site Art Space, the Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA Berlin), and the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA PS1) in New York. Some of the Chinese translations refer to the exhibition documentation of Para Site Art Space.https://www.para-site.art/exhibitions/offerings-for-escalante/

[2] The term ‘Bungkalan’ comes from the Tagalog verb bungkal, which means ‘ploughing the soil’ or ‘digging’. Reference source: Ami Lien and Enzo Camacho, ‘Surviving Tiempo Muerto: On Bungkalan and Peasant Resistance in the Philippines,’ Artist Op-Eds, Minnesota: Walker Publishing, 2020. https://walkerart.org/magazine/amy-lien-enzo-camacho-bungkalan-peasant-resistance-phillipines-artist-op-ed

[3] Caev Solas, ‘Bungkalan: When the Filipino peasantry tries to assert their rights’, Institute for Nationalist Studies, Medium, 2022. https://ins-ph.medium.com/bungkalan-when-the-filipino-peasantry-tries-to-assert-their-rights-7e55c227fc35; Carlos H. Conde, ‘Philippine Sugar Plantation Massacre: Negros Killings Spotlight Peasants‘ Long Struggle for Land’, Human Right Watch, 2018. https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/10/22/philippine-sugar-plantation-massacre

[4] Saidiya Hartman proposes the method of ‘critical fiction’ in ‘Venus in Two Acts’. In reference to enslaved black women, she advocates extracting basic elements from archival documents and then reorganising and imagining them, ‘telling an impossible story and amplifying the impossibility of storytelling’, thereby reconstructing ‘possible history’ and countering archival violence. For details, see: Saidiya Hartman, ‘Venus in Two Acts,’ ‘ Small Axe, Duke University Press, Number 26 (Vol. 12, No. 2), 2008. pp. 1–14; and the Chinese translation of ‘Critical Fabulation’ is referenced from the first issue of the Guangdong Times Museum online journal ‘South of the South’https://www.timesmuseum.org/cn/journal/south-of-the-south/venus-in-two-acts

[5] According to the research of the artist Karel Doing, ‘Phytogram’ is a technique that uses the chemical composition of plants to create images on photographic emulsions. Reference source:https://phytogram.blog/research/

[6] Ami Lien and Enzo Camacho, ‘Surviving Tiempo Muerto: On Bungkalan and Peasant Resistance in the Philippines’, Artist Op-Eds, Minnesota: Walker Publishing, 2020. https://walkerart.org/magazine/amy-lien-enzo-camacho-bungkalan-peasant-resistance-phillipines-artist-op-ed

Artist Duo_

Ami Lien (American, born 1987)

Enzo Camacho (Filipino, born 1985)

Venue_

Gallery of Modern Art, Glasgow, United Kingdom

Year_

Jun 07 – Sep 01, 2024

(Presented by Glasgow International with Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA). The central film, titled Langit Lupa, is co-commissioned with Para Site Hong Kong, CCA Berlin – Centre for Contemporary Arts, and MoMA PS1)